Strategic Insights into the Bottom of the Pyramid

Background

C.K. Prahalad’s “Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid” has received praise and disdain for its ingenuity and exaggerated optimism, respectively. The altruistic concept that poverty can be transformed into opportunity is attractive and Prahalad’s case study evidence demonstrates support.[i] Through an examination of support, criticism, and current business practices, this paper recommends when and how the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP) should be targeted to minimize risk and maximize profit opportunities.

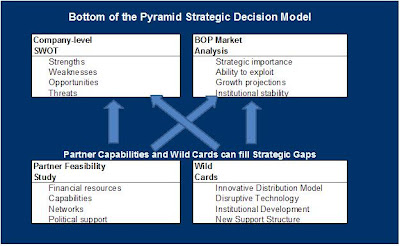

Prahalad asserts that the BOP offers opportunities for profitability while achieving social good and that profit-seeking MNCs are the best means to achieve this. Aneel Karnani, a fellow Ross School academic, argues that Prahalad has vastly overestimated the market opportunity, that the case studies presented do not prove the stated points, and that in order for the poor to afford goods currently out of reach MNCs must reduce quality. Both arguments have merit, and out of a balanced understanding of risks and opportunities a framework can be applied to evaluate strategic options (see Exhibit A).

Importance of Localization

In identifying the continued importance of physical location in business, with preferences towards an increasingly localized market, Pankaj Ghemawat supports the idea that multinational corporations (MNCs) cannot conquer the world without catering to local markets.[ii] Nowhere is this more valid than in the BOP, where tastes and preferences are traditionally less influenced by branding. Patrick Cescau, the boss of Unilever, host of a hallmark BOP success story, agrees, “The traditional multinational model of local subsidiaries operating with globally-imposed processes, capabilities, structures and branding is not up to the job in these low-income markets.”[iii] This was learned after Nirma, an indigenous Indian low-quality soap brand, increased market share from 12% to 62% between 1977 and 1987 while Surf, Unilever’s offering, shrank from 31% to 7% over the same period.[iv]

Prahalad’s assertion that BOP markets face less competition because MNCs have largely ignored them is challenging to generalize. For every underserved market there are rising indigenous companies that may be better suited to realize new opportunities in the midst of institutional voids. Emerging market companies have the knowledge and experience to navigate through these voids while utilizing talent and capital from developed markets to position customized solutions for local markets.[v]

Synergistic Partnerships

Different local requirements of resources and capabilities to reach BOP markets increase the importance of partnerships. Oftentimes, a for-profit MNC can achieve its revenue and profit goals by helping NGO’s achieve their social goals. For example, Telenor partnered with Grameen Bank to provide phones to budding entrepreneurs, as the “village phone lady” emerged. By demonstrating a social good byproduct, Telenor was able to shift some risk from its venture to public funding. Similarly, Map Agro was able to help Waste Concern, a non-profit focused on removing waste and improving sanitation of slums in Bangladesh, by purchasing waste at a discount and converting it to organic fertilizers, sold to local farmers at a profit. Map Agro gained goodwill from the government of Bangladesh, enabling smooth business license approvals and access to free land for composting. Map Agro had previously focused on chemical fertilizers, but had the distribution channels in place to provide organic compost to farmers.[vi] By recognizing the mix of goals, capabilities and weaknesses of different players in the marketplace, strategic alliances can be structured to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes.

Recognizing changing political and social trends can create opportunities for managers evaluating partnerships for BOP opportunities. Linking to the Millennium Development Goals or NGO’s engaged in social entrepreneurship may offer access to funding and free resources. Hindustan Lever’s success in creating job opportunities for entrepreneurs funded by the microfinance revolution is an example. By including job opportunities and income generation at the BOP as strategic imperatives, companies can increase their customer base and ensure revenue continuity. Managers should recognize and respond quickly to changes in the political environment and partner organizations; knowledge feedback loops enable agile decision making.

Disruptive Technologies

Karnani is correct in arguing that without new technological or institutional developments, opportunities are limited. However he may be shortsighted in asserting that new technologies are unlikely to develop in product areas beyond electronics and telecom.[vii] Disruptive technologies are valuable in BOP markets for multiple reasons: 1) they may unlock potential unavailable to existing products and services, 2) BOP customers have no reference point to existing offerings and thus less of a hurdle than developed markets, 3) they can lessen competition to enable a foothold from which to launch upstream marketing. However, venture capitalists may shun this approach because BOP markets may require a longer than average time horizon to reach profitability and disruptive technologies may limit the pool of potential acquirers, as they tend to reduce the value of existing offerings. Additionally, venture financiers may view social benefits as profitability not captured, and therefore at odds with their financial return motive.[viii] This finding means that venture-backed firms may be at a disadvantage to both small firms with financially supportive partnerships and stronger MNCs.

Strategic Fit of BOP Markets

Some argue that the near-term profitability is irrelevant for BOP opportunities, given the long-term strategic importance of reaching the next generation of mainstream consumers.[ix] This concept is challenging for managers under pressure from public shareholders for short-term results. To evaluate whether venturing into the BOP aligns strategically with a company’s imperatives, managers must determine the value that its shareholders put on corporate social responsibility, risk tolerances, and profitability time horizons. Hindustan Lever launched their Shakti project to sell products in rural villages through local entrepreneurs funded by micro-lenders. Their success was anchored in long-term benefits of branding to an expanding middle class as much as short-term profitability (evidence of profits is anecdotal). The company has received significant publicity for its innovative and socially responsible efforts that is likely to pay financial dividends in the form of brand loyalty for years to come.

Generalizing about BOP markets has been criticized due to the lack of cross-market success stories. Hindustan Lever began working with Indian rural development in the 1970’s and the Shakti project was initiated in 2001, but as of August 2008 no efforts to internationalize the project have been undertaken, likely due to the different opportunities and challenges across different regions and locales. Unitus is a “microfinance accelerator” that has developed a framework to qualify microfinance institutions for management support, best practice sharing and application, and funding.[x] The very concepts that screening frameworks can be applied and best practices can be shared throughout a BOP industry demonstrate that there are similarities between BOP markets. However, microfinance seems to be alone as an example of expanding BOP strategies across emerging markets, showing that knowledge transfer and scalability can be challenging.

Conclusions

Companies should consider the BOP as either a market or a source, and as a testing ground for new technologies and products. It is important to consider a company’s capabilities and gaps, and find partners to plug the gaps rather than investing heavily to develop new capabilities. Companies should be prepared to invest for the long-term, given that rapid profitability growth has been elusive. In the same vein, evidence that BOP markets can reduce overall risk is lacking, as the global economy seems to be inextricably tied and new markets tend to carry less certainty.

To evaluate BOP opportunities, the “Bottom of the Pyramid Strategic Decision Model” found in Exhibit A is recommended. Through a SWOT analysis, managers are encouraged to evaluate weaknesses or gaps that may filled by either a partner or a change in the competitive environment, referred to herein as a “wild card.” Similarly, once capabilities are determined, the value of specific markets should be evaluated in the context of available partners and wild cards. For example, if a medical product manufacturer has developed a breakthrough low-cost solution, but lacks a distribution mechanism, they may partner with an existing NGO that has access to needy markets. Additionally, if an East African nation was identified as the market with highest demand but political and legal institutions were lacking, it would be recommended to wait until stability was achieved or partner with an organization that can boost stability, such as USAID. Significantly, companies have the ability both to observe and capitalize upon these wild cards, but also to drive them to fruition and change BOP markets. By introducing a new technology, implementing a new distribution model, garnishing support from local institutions thereby adding stability, or bringing publicity and public funding to a need, astute managers can tilt these often flexible market structures more so than in developed markets. By recognizing BOP opportunities and risks and innovatively combining resources inside and outside the traditional MNC box, profitability can be achieved by corporations while social goals are achieved by partner organizations.

[i] Prahalad, C.K. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Upper Saddle River: Wharton School Publishing, 2006.

[ii] Ghemawat, Pankaj. “Why the World Isn’t Flat.” Foreign Policy 159 (2007): 54-60.

[iii] Mitchell, Alan. “The bottom of the pyramid is where the real gold is hidden.” Marketing Week 30.6 (2007): 18-19.

[iv] Karnani, Aneel. “The Mirage of Marketing to the Bottom of the Pyramid: How the Private Sector Can Help Alleviate Poverty.” California Management Review 49.4 (2007): 90-111.

[v] Khanna, Tarun and Krishna G. Palepu. “Emerging Giants: Building World-Class Companies in Developing Countries.” Harvard Business Review October (2006): 60-69.

[vi] Seelos, Christian and Johanna Mair. “Profitable Business Models and Market Creation in the Context of Deep Poverty: A Strategic View.” Academy of Management Perspectives 21. 4 (2007): 49-63.

[vii] Karnani, Aneel. “Misfortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid.” Greener Management International 51 (2006): 99-110.

[viii] Harjula, Liisa. “Tensions between Venture Capitalists’ and Business-Social Entrepreneurs’ Goals.” Greener Management International 51 (2006): 79-87.

[ix] Mitchell, Alan. “The bottom of the pyramid is where the real gold is hidden.” Marketing Week 30.6 (2007): 18-19.

[x] Unitus. “Unitus - What We Do: Accelerate Microfinance Growth.” Accessed August 19, 2008. http://www.unitus.com/unitus-in-action/what-we-do/accelerate-microfinance-growth.

Exhibit A

No comments:

Post a Comment